Twelfth Night

Live Theater As Theater of Lives

Fiasco Theater, Classic Stage Company, New York, New York

Friday, January 5, 2018, B–203&204 (middle center of deep thrust theater)

Directed by Noah Brody and Ben Steinfeld

The Shakespeareances.com Canon Project: 38 Plays, 38 Theaters, 1 Year

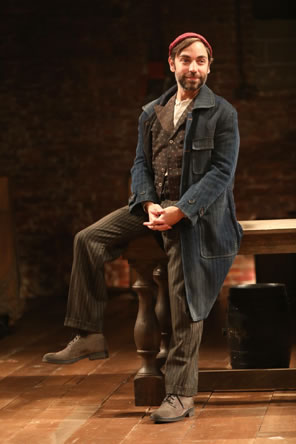

Ben Steinfeld plays a fourth-wall straddling Feste in Fiasco Theater's production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night at Classic Stage Company in New York. Photo by Joan Marcus, Fiasco Theater.

"For what says Quinapalus?" Feste, the household jester (aka, fool), asks rhetorically, looking around the room. OK, apparently not rhetorically. The room Ben Steinfeld's Feste is perusing in Fiasco Theater's production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night at New York City's Classic Stage Company (CSC) is not an imagined one in Olivia's house but the theater itself with some 199 people filling every seat on three sides of the deep-thrust stage. That audience remains silent, so Steinfeld says, "I'll remind you," a non-Shakespearean line eliciting a laugh before he gets back to Shakespeare's text: What Quinapalus says is "Better a witty fool than a foolish wit."

Fiasco Theater, a New York–based troupe of young actors, has emerged as one of the world's leading Shakespeare practitioners. This Twelfth Night further cements that status. Steinfeld, typical of the rest of the company, is a richly talented actor so studied in interpreting his Shakespearean characters' verses that Feste's warped ideas and obtuse references make logical sense (this Feste would make a helluva lawyer). Almost all his jokes land with laughs, too. Yet all the while, Steinfeld—or, rather, Feste—acknowledges that he is performing in a play before an audience, merging stage fiction with theater reality. This Twelfth Night is full of such moments, many contributing to the palpable sense that though this is the 27th stage production of the play I've seen, I came away feeling it was the first time I got the whole story.

I'm an unabashed fan of Fiasco Theater. We squeezed in a trip to New York at our busiest time of the year to catch a performance at the end of the play's CSC run as the kick-off for Shakespeareances.com's Canon Project: 38 Plays, 38 Theaters, 1 Year. I've now seen all of Fiasco's Shakespeare productions, the first three using a cast of six—Measure for Measure, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, and Cymbeline (the last a critics' darling that put Fiasco on the New York theater map)—as well as its production of Stephen Sondheim's Into the Woods using 10 actors and a pianist. These brief descriptions might wave red flags before Shakespeare purists who scream "gimmickry" at the mere mention of reduced-cast or regendered productions.

However, what I love most about Fiasco—even given the company's immense acting and musical talent—is how those actors, led by co-directors Noah Brody and Steinfeld (both founding company members along with Jessie Austrian), take a disciplined, exploratory approach to Shakespeare's texts. They uncovered dimensions of society's stratifications in Measure for Measure through the play's juxtapositions of private and public life and the constant conflicts waged among the mind, the soul, and the groin. They revealed the flaw-filled human nature that drives the behavior of every character in The Two Gentlemen of Verona. They not only made sense of Cymbeline's plot, they turned it into a popcorn adventure thriller with one trunk on a bare stage (albeit, that was one amazing, multitasking trunk). All well and good for three of Shakespeare's lesser-known works; this is Twelfth Night, number four on Shakespeareances.com's Shakespeare Plays Popularity Index. What could they possibly bring to this play that hasn't already been done, even as they expand from their six-actor core company with a cast of 10?

The point is, they don't "bring" anything to Shakespeare's plays. They embrace what's there in the text, to every last detail—including clues to what on the surface seems to be missing information (when Shakespeare wants to give you a backstory, he goes to great lengths to do so).

Fiasco dresses its Twelfth Night in a mid-20th century, northern British or New England seaside look that serves the play's gender politics while avoiding cultural anachronisms with a sometime-ago-in-another-place feel. Scenic Designer John Doyle clutters the stage with crates, barrels, lobster traps, rustic furniture, ropes, and metal chandeliers. A ship's wheel shrouded in fishnet leans against an upright piano at the back of the stage where other musical instruments are arrayed. Costume Designer Emily Rebholz employs muted browns and greens for Orsino's landed-gentry vest and slacks, Olivia's country living designer dresses, and Viola's and Sebastian's cable-knit sweaters. Malvolio (Paul L. Coffey) is more formally attired in black tux and tails, and his "yellow stockings" is a seaman's rain slicker, complete with rubber boots and yellow hat—and his legs cross-gartered. It's entirely too ridiculous, but Coffey, a core member of Fiasco, hitherto has used physical nuances in his portrayal of Olivia's steward to arrive at this point when he has cast off all notions of decorum and place, not only by reading the faux love letter that Olivia's waiting woman, Maria (Tina Chilip in her Fiasco debut), has planted for him but also by misreading the essence of his relationship with Olivia.

Olivia (Austrian) relies on Malvolio to not only run her household but represent her when touchy situations merit, such as dismissing the duke's messenger, "returning" the duke's ring to the messenger, and encouraging Olivia's drunk uncle, Sir Toby Belch (Fiasco core member Andy Grotelueschen) and his cohort Sir Andrew Aguecheek (Paco Tolson making his Fiasco debut) depart the house. Her relationship with Malvolio requires intrinsic trust, but not necessarily love or even fondness. Coffey's Malvolio is initially careful not to overstep his boundaries. After Malvolia upbraids the carousing Toby, the knight hands Malvolio a tray, causing Coffey to noticeably stiffen in a posture of attention to rank as Toby asks, "Art any more than a steward?" But, when Toby asks Maria for another stoup of wine, Malvolio sees his break: he presents the tray to Maria by way of establishing his rank over her and thereby re-establishing his ultimate power, via his standing with Olivia, over Toby. Nevertheless, Malvolio's own ambition and arrogance leads him to perceive Olivia's trust and respect as fondness, and Maria's letter sprouts that perception into love, which leads him to disaster.

Similarly, Olivia's relationship with Feste has subtextual resonance, as revealed by Austrian and Steinfeld. Feste took an unexplained leave of absence long enough to anger Olivia, who is mourning her brother's death, which came shortly after their father had died. The extent of Olivia's anger is evidenced in Maria warning Feste upon his return that he could be hanged or turned out. Feste is confident—publically, at least, if not in his own mind—that he can win Olivia over, and Steinfeld reinforces Feste's sureness in the way he turns his invocation of Quinapalus into a metatheater moment. Olivia arrives and confirms Maria's warning; immediately upon seeing Feste, Olivia orders that the fool be taken away. Feste fends off her order with dexterous riddling and then gets her to agree to be proven a greater fool than he, which he does, dangerously, by stating that the brother whose death she is mourning has gone to hell. "I know his soul is in heaven," she snaps back. "The more fool, madonna, to mourn for your brother's soul being in heaven."

It's one of the play's more famous jokes, but Austrian also makes it a milepost moment in Olivia's arc. This Olivia is a romance-infatuated young woman with a pleasant disposition trying to emerge from her state of mourning; Feste's absence apparently forestalled that. She seems eager to have him prove her a fool, and when he does, not only does her manner immediately relax, she juxtaposes Feste with her overly serious steward: "What think you of this fool, Malvolio? Doth he not mend?" (implicating, perhaps, that Malvolio was the one who suggested Feste be hanged or turned out). In subsequent lines, Austrian's Olivia and Steinfeld's Feste display a close fellowship, he her confidante, she his validator (and Malvolio, not being present at that moment, might not be fully aware of this relationship's depth).

With her fool back in the fold, Olivia tilts toward solace if not happiness, which opens her to being intrigued by the saucy messenger at the gate. Though she knows it is another unwanted love emissary from Duke Orsino, Olivia opens her gates to the messenger, thereby unlocking the gate to her heart, too. Upon meeting Viola, disguised as Cesario, Olivia's fascination turns to infatuation. She can't help it, not in the way Emily Young, another Fiasco regular, portrays Viola in this scene. Starting into her “willow cabin” speech, Young's Viola crosses the stage to stand in front of Olivia, then grabs hold of the lady’s shoulders and looks deeply into her eyes as she hallows Olivia’s name to the reverberate hills. Viola is all-in, not just representing her master in sentiment but in passion, too—and being a woman, she knows what works. Boy does it work on Olivia—except that she is not looking beyond the face in front of her. This is the key emotional turning point of the play, as Olivia is swept away into the realized bliss of all her tween-like romantic yearnings, an electric moment she never will be able to shake despite obvious obstacles, not the least of which is that Viola/Cesario rebuffs her..

Fiasco was formed from ensemble DNA, which dictates the troupe's choices of and approach to its productions. Whether in a cast of six or 10, with core members or with additional or substitute actors, individual performances fit in with ensemble dynamics not so much like puzzle pieces but as a loom turning different-colored yarn into a single, unified experience. Even Brody’s Orsino, who remains isolated until the last scene (sometimes physically, but always emotionally walling himself off from everybody else), melds with the other portrayals in other scenes throughout the play. Though he's not on stage at the time, we see him in our mind's eye in Olivia’s determined claim that “I cannot love him. Yet I suppose him virtuous, know him noble of great estate, of fresh and stainless youth;in voices well divulged, free, learn'd and valiant; And in dimension and the shape of nature a gracious person: but yet I cannot love him."

Many may want to soften Orsino’s edges, but Shakespeare won’t let you: the duke too often behaves as a tyrant and is always self-centered. In this day he could be accused of stalking. But as Brody portrays him, we not only can see why Olivia can’t love him (and credit her sensibility in that) but why Viola does. She’s spent much time in his company, has seen as well as heard his passion, watched him sob uncontrollably after Feste sings “Come away, death,” and knows the romantic volume of his heart. His passions may run the gamut of extremes, but they always center on a yearning for perfect love—a sentiment he shares with Olivia, by the way (in this day, she could be accused of stalking, too). Just as Austrian plays out Olivia's personal milepost moment, so Brody displays the transition to maturity that has been wanting in Orsino's life, when the picture of love he has been chasing suddenly gives way to understanding what he has been feeling since Cesario arrived at his court. As Viola and Sebastian (Javier Ignacio) reunite in the final scene, at the back of the stage Brody's Orsino bears an emoji face of shock dawning into realization. Meanwhile, Austrian's Olivia giggles uncontrollably, seeing two Cesarios ("Most wonderful!") even as her mind absorbs the awkward implications of what she's witnessing.

Top, from left, Sir Toby Belch (Andy Grotelueschen), Sir Andrew Aguecheek (Paco Tolson), and Fabian (David Samuel) spy on Malvolio from the balcony, replacing the box tree of the gulling scene in Fiasco's production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night at Classic Stage Company. Above, the ensemble sings: from left, David Samuel (at the back playing piano), Ben Steinfeld (guitar), Javier Ignacio (violin), Jessie Austrian, Noah Brody, Paco Tolson, Emily Young, Paul L. Coffey (cello), Tina Chilip, and Andy Grotelueschen. Photos by Joan Marcus, Classic Stage Company and Fiasco Theater.

Sirs Toby and Aguecheek don't have any such milepost moments: they already are what they will be. Grotelueschen's Toby maintains a perpetual squinting grin, approaching his existence as the be-all of living large, imparting an air of superiority undergirding his aspect of congeniality. Yes, he’s fleecing Aguecheek, but it's more for the fun and intellectual exercise of it than mean-spirited. Playing Aguecheek, Tolson balances exaggerated clowning with character-driven line readings. He is the centerpiece of the longest sustained laugh of the show as Maria, Feste, and Toby all hide in a line behind Aguecheek when Malvolio bursts in on their carousing: Tolson's Andrew is stuck at the front with an uncomfortable expression somewhere between fear and oblivion as he sustains the full force of Malvolio's wrath directed through him at Toby. Tolson's portrayal reaches perfect harmony on his line “I was adored once, too.” I’ve seen this delivered with everything from pitiable pathos to flippant silliness, but Tolson gives it poignant nonchalance as he speaks from a heart of disappointment but with a mind of casual indifference. This Aguecheek knows exactly what he is, as he often admits: "'Tis not the first time I have constrained one to call me knave," he tells Feste, and in the box tree scene he admits, "many do call me fool."

Aguecheek along with Toby and Fabian (David Samuel) are not in a box tree as they watch Malvolio read Maria's "obscure epistle of love"; Maria has told them, rather than "the box tree," to hide in "the balcony" of the theater. That's a slight adjustment to Shakespeare's text, but as the cast weaves Shakespeare's romantic tapestry, they keep it affixed to its frame, the theater itself, while the audience is integral in the warp and weft of the piece. That's another trademark of Fiasco's productions. The cast mingles with patrons before starting the play and during the intermission. Actors sit in view at the back of the stage playing instruments or providing sound effects when their characters are not on stage. Grotelueschen often gives actor asides: "My god, there's so much bread," he mutters as he gathers up the loaves he and Maria had thrown at Malvolio. Young's Viola twirls to catch a sword Toby has winged her way and says "you're welcome" to the audience members sitting behind her. After his Feste plays the curate visiting the imprisoned Malvolio, Steinfeld runs on stage with his guitar for a song "while they move the furniture," which the rest of the cast is doing. "This is for Sir Topaz," he shouts, and launches into the Arlo Guthrie version of "(Give Me That) Old-Time Religion," getting the audience to sing along. That's not Shakespeare, but it's not necessarily Steinfeld, either; it is Feste straddling the so-called fourth wall.

Fiasco even uses doubling for thematic purposes, and so it is here. When Toby decides to continue pranking Malvolio by having him committed to a cell, disapproval crosses the face of Samuel's Fabian, reflecting the opinion of many critics who believe Toby's malice goes too far. Fabian is then absent from Toby's further hijinks, a thematic tint to theatrical reality: because Samuel is doubling as Antonio, his Fabian can't be in the upcoming duel scenes. Maria takes Fabian's place for the duels, and she also replaces Fabian in the final scene (in which Antonio is again present). It's fun to watch Chilip's precious expression as her Maria listens to Olivia read Malvolio's letter (Fabian's assignment in Shakespeare's text) and then explain the purpose of the joke and her role in it through "Sir Toby's great importance, in recompense whereof he hath married me. Yay," she adds after an uncomfortable pause—again, a tweak of the text, but multicharacter-driven funny.

And respectful—of Shakespeare, of the play and its characters, of theater and the audience. As an art form, theater is a living, breathing thing. Fiasco doesn't so much breathe new life into plays as resurrect the lives Shakespeare has written into the text.

Eric Minton

January 11, 2018

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances