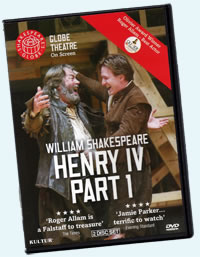

Henry IV, Part One

The Lie Is the Truth

Kultur/Shakespeare’s Globe (2012)

Directed by Dominic Dromgoole, with Roger Allam, Jamie Parker, Oliver Cotton, Same Crane, Barbara Marten, William Gaunt.

When Dominic Dromgoole’s production of Henry IV, Part One, comes to its two moments of truth, falsehood carries it through. The first moment comes when Falstaff has been caught in his mountain of lies about what really happened during the Gads Hill robbery, and his final assertion that he knew all along it was the prince who ambushed him earns applause from the audience. The second moment comes in the final act when Falstaff so effectively fibs about killing Hotspur that Hal, certain he killed Hotspur himself, nevertheless grants Falstaff the honor of the victory. Falstaff can charm audience or a fellow character even with the most blatant of his lies.

When Dominic Dromgoole’s production of Henry IV, Part One, comes to its two moments of truth, falsehood carries it through. The first moment comes when Falstaff has been caught in his mountain of lies about what really happened during the Gads Hill robbery, and his final assertion that he knew all along it was the prince who ambushed him earns applause from the audience. The second moment comes in the final act when Falstaff so effectively fibs about killing Hotspur that Hal, certain he killed Hotspur himself, nevertheless grants Falstaff the honor of the victory. Falstaff can charm audience or a fellow character even with the most blatant of his lies.

The second moment is the trickier, as it proves a pivotal point in Jamie Parker’s evolution as Hal in this play, but both moments succeed specifically because Roger Allam’s Falstaff is as effective a liar as any stage will ever see.

This production, which ran at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2010 and earned Allam an Olivier Award for Best Actor (London’s equivalent to the Tony Awards), is now available on DVD. Filmed before a live audience at Shakespeare’s Globe, this DVD is a treasure if for no other reason than the rarity of having this great play filmed. The 1979 BBC/Time-Life production gives us the incomparable Anthony Quayle as Falstaff, a wonderful Hotspur in Tim Piggot-Smith, and Jon Finch continuing his role as Henry Bolingbroke from the series’ sublime Richard II installment, but poor production quality and a dubious performance by David Gwillim as Prince Hal are unfortunate detractions. This Shakespeare Globe production also has some detractions (and distractions), too, but most of it is thumbs-up quality.

The acting is five-thumbs-up worthy, starting with Allam. People familiar with London theater over the years know of Allam’s talent, which was put to especially good use at the Royal Shakespeare Company (I’ve seen him as Brutus, Toby Belch, Measure for Measure’s Duke, and Clarence in the Antony Sher Richard III, and he was the original Inspector Javert in the stage musical version of Les Misérables). Allam’s Falstaff is the gregarious fat fellow who establishes himself as the life of the party, presides over the fun, tells most of the jokes and one-ups others’ jokes, and has enough intelligence (at least more than his fellows) to wittily comment on any and everything. You might dread having him in your company, and your recollections of his company might be cringeworthy, but when you're with him you can't help enjoying his company.

What sets Allam’s Falstaff apart from your normal alpha walrus is how brilliantly he lies. Allam fully captures Falstaff’s disingenuousness; he may tell Hal that thieving is his vocation but, really, equivocation is his true vocation. Furthermore, it is in the dexterity with which he performs his falsehoods that we can’t help admiring him. Take his final scene in this play. We know Hal killed Hotspur; we even hear Falstaff tell us he will claim that Hotspur “counterfeited” death and rose to fight again, and he gives the corpse a false wound. Yet, when Hal and his brother John return to the stage and hear Falstaff’s version of events, even we, the audience, are swayed. Allam’s Falstaff lies so effectively that, like John and Hal, we feel powerless to contradict him. “Is not the truth the truth?” Falstaff says (even as he’s lying at the time), and the brilliance of Allam’s performance is that while his Falstaff knows the answer is “no,” he nevertheless convinces us the answer is “yes” even when we know better.

Hal’s reaction in Falstaff’s final scene is telling, and it brings to fruition a portrayal of the prince by Jamie Parker that had seemed uneven in the first few scenes. Turns out it may be Hal who is uneven or maybe manic. In the play’s first half, Parker’s Hal giddily squeals and dances like a drunken 14-year-old on his birthday, idiotically fools around with Falstaff at Gads Hill, and cruelly baits the simple Francis (Joseph Timms) in a prank at the Tavern. Yet in the flash of a line Parker’s Hal grows sullen, pouts, or erupts in unexpected anger. In the Eastcheap scenes in the first half of the play, Parker’s Hal clearly hates being Prince of Wales. His “I know you all” speech is more of a wailing lament than a proclamation of calculated strategy; he knows his fate and if he is to have any kind of security he has no choice but to “imitate the sun” and emerge from the clouds of his preferred lifestyle. In speaking the emotional lynchpin line pertaining to banishing plump Jack, this Hal says “I do” to cut off Falstaff’s schtick, and then his “I will” is a statement of fact: banishing Falstaff is his inevitable duty. Not that he likes it.

Hal’s turnaround comes in the scene with his father. At first he’s the sullen son wearing a “yeah, I’ve heard this before” attitude that drives any dad mad. After his father's first remonstration, Hal replies almost flippantly that he’s been kind of truant, yeah, but not as bad as people might be saying, so “wherein my youth hath faulty wandered and irregular, find pardon on my true submission.” King Henry roars full force in the prince’s face: “God pardon thee!” Whoa. Hal is shocked into submission. He listens in agitation as Henry compares his son with himself, becomes upset when dad starts comparing him to Hotspur, and boils over when the king suggests that Hal is a bigger enemy than Hotspur ever could be. “Do not think so,” Hal retorts, exploding from his chair, and then, desperately, “you shall not find it so.” His reply is not wholly convincing, especially for the wary king, but it is the beginning of Hal’s redemption. The rest of Hal’s journey through the battle at Shrewsbury sees Parker maturing as a soldier (initially he seems understandably scared to go to war) and gradually tempering his madcap manners in Eastcheap. From disappointment early in the play, I arrived at appreciation of Parker’s portrayal by play’s end—and that’s evidence of how well the actor manages this complex interpretation of Shakespeare’s complexly drawn Prince of Wales.

Oliver Cotton plays Henry IV with a regal bearing—there’s nothing pathetic about him. Rather than shaping him as a conniving politician or a guilt-plagued king, Cotton anchors his portrayal in the king’s role as a father. In the confrontation with Hal, Henry’s description of his own rise to power is not self-aggrandizement or political mentoring but a rant driven by disappointment in his son. He even takes a father's tone in his treatment of Hotspur—Northumberland’s young Harry whom the king wishes he could switch with his own Harry. When Hotspur refuses to give up his prisoners, King Henry does to him exactly what he later will do to Hal: bend over and bellow in his face. The effect is the same, too, cowing the young Harry. (Falstaff even imitates this trait of Henry’s in the play-acting scene with Hal.)

This production is particularly respectful of the play’s older men. Aside from Falstaff and King Henry, top quality performances are turned in by William Gaunt as a heroic Worcester and Christopher Godwin as Northumberland, trying to keep up with the shifting politics while corralling his own son.

Roger Allam as Falstaff in Henry IV, Part One. Photo by John Haynes, Shakespeare's Globe Theatre.

The portrayal of that son, Harry “Hotspur” Percy, is this production’s confounding thumbs down. Not to fault Sam Crane, for his acting skills are apparent, but the interpretation of Hotspur as an intensely malevolent dogmatist and novice politician saps the character of any of his charm. This is the second text-centric production we’ve seen in succession that portrays Hotspur this way, so maybe I'm wrong in my long-held interpretation of Harry Percy as a hotheaded but personable warrior with a blinding devotion to honor and absolute impatience for frivolity (be it politics, music, or Glendower’s fancies). Both attributes make him heroic and funny, and both prove to be his tragic flaws, too. If Shakespeare did not intend that, then why would such a spitfire as Lady Percy (and Lorna Stuart plays her as a real spitfire) love this killjoy, this egomaniac, this antiromantic, this bully, this tightly wound ball of intensity, this vicious twit? Crane’s Hotspur even moves to strike her when she won’t sing in the Welsh scene. His lines certainly can be played that way, but everybody else, even the king, regards Hotspur with some affection in addition to respect. And I believe Shakespeare regards him affectionately, too. Take Hotspur too seriously and you lose, as this production does, the comedy in the Popinjay speech, in the subsequent rant with his uncle and father, in the horse quibbling with Lady Percy, in the Welsh scene, and in the prebattle scenes at Shrewsbury featuring Hotspur’s let’s-measure-’em interactions with the Douglas (Phil Cheadle ever-emoting virility) and Vernon (Kevork Malikyan in a portrayal of steeled sensibility).

Henry IV, Part 1, is, in fact, Shakespeare’s most clever character-driven comedy, matched in quality as a comedy only by Twelfth Night. Its humor runs through every scene except for the meeting between Henry and Hal (even Hotspur’s death generates humor as he expires before he can finish his last pronouncement of bravado, which Hal concludes for him with “worms”). Like all of Shakespeare’s comedies, this play has an undertone of tragedy, and as a history it interweaves the national lesson with laughs. In Dromgoole’s take, the Falstaff story is a comedy set off against the serious intensity of the Hotspur story. That’s, respectively, good and bad.

In between, Dromgoole deftly delivers the story of Prince Hal, ruffian prince who matures to become England’s greatest king. When last we see him in this play, he reluctantly gives in to Falstaff’s crowning lie and gains just a portion of his father’s confidence. How does Hal evolve from here? We don’t have long to wait, for the DVD of Henry IV, Part Two, was released the same time as Part One. Grab another glass of wine or cup of tea. Part Two awaits.

Eric Minton

August 9, 2012

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances